Photo credit: National Education Association

BY DJ LEE

Until 1850, Oak Park, Illinois, where I’ve lived for 20 years, was an oak and hickory savannah. Some of those old trees are still standing. Called “remnant trees,” they rooted themselves here before the arrival of white settlers in the 1830s.

I can only imagine what those trees have seen!

Every day this past summer, I visited a bur oak remnant on North Kenilworth Avenue a mile from my house. Arborists believe this oak was also a Witness Tree of the Potawatomi. It marked the spot that led people home to the Des Plaines River after a day of hunting and gathering.

Oak Park may be the place from which Ernest Hemingway and Frank Lloyd Wright shot to stardom, but these men are minor lights in the village’s larger constellation. Oak Park is known principally for its trees and its housing policies. Around 19,000 trees currently fill a one-and-a-half by three mile rectangle, and that’s just along the parkways and public spaces. The neighborhood also prides itself for its fair housing ordinance developed in the 1950s and 60s during Civil Rights. Yet Oak Park, like much of the US, is to this day marred by the insidious practices of redlining.

*

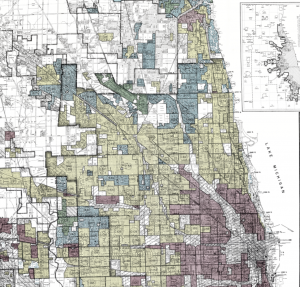

Above is a 1940 map of Chicago from Mapping Inequality, a site mounted to show the history of redlining. As Ta-Nehisi Coates points out in his article in the Atlantic, redlining was based on the Federal Housing Administration’s “system of maps that rated neighborhoods according to their perceived stability.” On this map, Oak Park is lauded for its “large, old trees,” yet it is colored yellow, meaning the neighborhood was “definitely declining” due to “infiltration of lower grade populations”—people of color and immigrants. Banks shied away from lending money to buyers in these areas.

*

My neighbor works for the Village of Oak Park. He’s the kind of person who knows his trees, knows their shapes, leaves, and bark, knows their names and has a special relationship with the varieties. Besides oaks, linden, maple, serviceberry, alder, birch, pear, bald cypress, pagoda tree, sweetgum, coffee tree, catalpa, poplar, honey locust, filbert, yellowwood, rubber, tulip, crabapple, and magnolia grow along not just the parkways and public spaces, but also in backyards, side yards, and front yards. When my neighbor’s Dutch elm got sick several years ago, he was devastated.

*

Though I’ve always admired Oak Park’s trees, that’s not why we moved here from the American West twenty years ago. We were drawn to the community who fought redlining and racism to build diverse and equitable neighborhoods. But Oak Park is not perfect. As I’ve found through the years, the mapped lines of racism are hard to redraw.

*

From my porch in Oak Park, I watched as tree doctors, including the village arborist, came to diagnose my neighbor’s Dutch elm and offer suggestions for its healing. My neighbor spent almost two years trying different remedies. Still, the tree died. I was home when the tree choppers came. My neighbor and I looked at one another through our glass doors and put our hands over our hearts. “Sad day,” I could see him mouth. When I stepped out the door, the tree men said, “Stay inside!” in stern voices as a huge limb came tumbling down.

*

I’ve learned more about Oak Park’s redlining practices and the fight to end them since we moved here. My neighbors, my daughter’s friends at Oak Park River Forest High School, the local museum, books like Austin Boulevard, the television miniseries This Is America, the documentary What Went Wrong in Chicago? America’s Most Segregated City, Ta-Nahesi Coates’s article “The Case For Reparations,” and the real estate woman who sold us our house have shaped what I know about the village and Chicago’s segregation practices.

*

In the 1960s, when Chicago’s city planners built public housing to continue segregation, and as redlining persisted unabated, a sizable portion of Oak Park citizens took action. Inspired by Civil Rights activists, black and white Oak Parkers staged demonstrations, led grassroots campaigns and educational meetings, and held fair housing rallies and sit-ins at real estate offices (realtors were complicit in segregating neighborhoods). They carried signs that read: “Closed to Negroes since 1917” as they marched down Lake Street, the village’s central thoroughfare, stopping at the real estate offices on North Avenue. The fair housing fight set neighbors against one another. I read letters in the local museum from 1963 protesting “integration.” I felt sick when I saw old photos of the firebombed house of Dr. Percy Julian, the brilliant black chemist, splattered across a dim sidewalk.

Despite these racist abuses, on May 6, 1968, Oak Park signed a Fair Housing Ordinance outlawing redlining.

*

At the same time as my neighbor’s elm started to wither, the lilac in our backyard took sick. We planted her when we first moved in. She’s a tall tree, grows straight and proud, unlike many lilacs, which are bushy and sprawling. But suddenly she was drooping under a thick dusty gray mold. We asked our neighbor for the name of his tree doctor. We scoured the internet for information. Sometimes lilacs can contract a mold disease. My husband and I thought we might have to cut her down. I felt the devastation in my own limbs as I examined hers. I just couldn’t.

And then, as if she were reading our minds, our lilac rallied, growing the fullest, most luscious blooms she’s ever produced. One flowery branch hung over the walk, asking to be noticed, acknowledged. She threw her purply-white scent everywhere, drenching us with love. “She’s trying so hard,” I told my husband. “She’s working to overcome the disease and share her beauty.” Instead of cutting her down, we watered her every day and lovingly spoke to her.

*

I didn’t make the connection between the elm and the lilac until later, that they may have shared a sickness. I somehow forgot how interconnected we all are. I didn’t consider what I already knew, that enormous mycorrhizal networks exist between neighboring trees. I’d learned this from a documentary called The Mother Tree Project. Through fungal systems under the Earth, trees interact with their neighbors, and it seems they do a better job than humans at this. They share resources, help seedlings grow, and alert each other to threats. They don’t view one another as individuals who are competitors for resources but as communal kin–maples, lindens, magnolias, elms, lilacs, and an ancient bur oak–a diverse collectivity.

*

After his Dutch elm was chopped down, my neighbor kept two large slabs of the trunk, each five feet in diameter. I used the photo I took of the elm slabs as background for charting my internal and external networks. The map (above) reminds me that between my human and tree neighbors are lines that must be redrawn.