Mary Swander and her play Vang (which BEI is bringing to Madison on April 19th, 2019) were recently featured in the Huff post! Read the article below or go to the original article here.

Iowa Laureate’s “Vang” Play Showcases Immigrant Farmers: Interview with Mary Swander

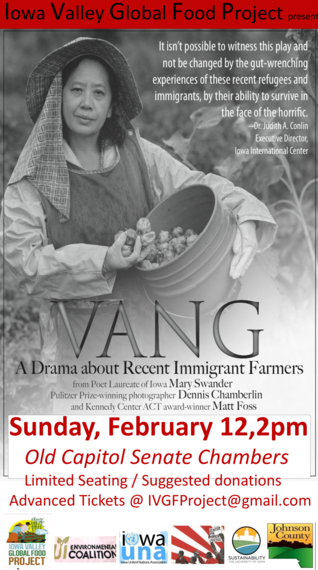

In a week of turmoil over federal immigration and refugee travel orders, Iowa poet laureate Mary Swander’s nationally touring play, Vang: A Drama about Recent Immigrant Farmers, is opening a new door to the extraordinary stories of families from Sudan, Mexico, the Hmong in Laos, and Holland that are quietly rejuvenating the state’s aging agricultural communities.

Swander, author of several acclaimed works of poetry and memoir, as well as the plays, Farmscape, Driving the Body Back and Map of My Kingdom, based Vang on three years of interviews and research with New Iowans across the state. Swander teamed up with Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Dennis Chamberlin and Kennedy Center award-winning actor Matt Foss to bring the stories of their journeys and the challenges of transitioning to farm life in Iowa to stage in Vang—a Hmong word for “garden” or “farm.”

Iowa, of course, has always been a crossroads of immigration—and a host of refugees.

“The immigration to Iowa this season is immense,” noted an Iowa newspaper in 1855, “far exceeding the unprecedented immigration of last year, and only to be appreciated by one who travels through the country as we are doing, and finds the roads everywhere lined with movers.”

The movers in Vang and Iowa today include Joseph Malual, a refugee from Sudan, who managed to work and earn a PhD in Sustainable Agriculture from Iowa State University, as well as Hmong families who have become mainstays in the Des Moines farmer’s market, and newly arrived Dutch dairy farmers in Brooklyn, Iowa.

Theatre productions of Vang have been staged across the country, as well as in smaller communities in Iowa. Swander often holds talk-backs on immigrant stories in the changing farm towns.

“We so rarely see ourselves reflected in the arts like this,” one of the audience members recently told her.

In advance of a special staging of Vang at the historic Old Capitol Senate Chambers in Iowa City on Sunday, Feb. 12, as a kickoff for the Iowa Valley Global Food Project, I interviewed Swander on her latest work and its impact on audiences across the country.

JB: The story of Iowa, in many respects, has been the arrival of immigrants as farmers, who have carried on the state’s agricultural legacy. After the success of your play, Farmscape, how did you happen to pursue the stories of four immigrant families for your Vang play?

MS: I wrote Farmscape with a graduate class at Iowa State University. We wound the play together from interviews of farmers and others involved in the changing rural environment. The students in my class were diverse in terms of gender, ethnicity, cultural backgrounds,religions, urban/ rural backgrounds , geographical parts of the country and the world. I urged the students to go out and find diversity in their interviewees, yet when they actually hit the pavement the first time, most returned with interviews of white male farmers with common opinions and values. The students had internalized society’s stereotypes of farmers.

So we worked with the material and looked at our own biases. We went out into the field again and broadened our search, and eventually came up with a play that hit on some of the major issues in contemporary agriculture. The play began touring and the state folklorist saw it and liked it. Then she suggested that in the future I might explore recent immigrant farmers. A few weeks later a new faculty member in photo journalism—Dennis Chamberlin—walked into my office and said he’d like to work with me. His two loves: sustainable agriculture and immigrants. An idea was born.

Dennis and I spent 3 years researching Vang. We read and read about immigration, the experiences of different immigrant groups to the U.S. and the culture, values, and folklore of various countries. I worked to find the immigrant farmers, develop trust and rapport with the interviewees. I interviewed scores of immigrant farmers and secured translators. I narrowed down my scope to the four couples profiled in Vang. I went back to each set of farmers 3-10 times. Dennis and I always went together at first, then we would each return separately.

I started out interviewing Hmong farmers at the Des Moines farmers’ market. With the help of a Hmong lecturer at ISU who grew up in the Hmong community in Des Moines, I finally settled on Toua and A Vang. An ISU Mexican graduate student in sustainable agriculture helped me find Ramona and Beni in Marshalltown. Dennis had photographed Joseph Malual for another project. Joseph and I often sat near each other in a weekly seminar at ISU—but little did I know his story. I had heard a story on Iowa Public Radio about immigrant Dutch farmers and Pat Blank opened the door for me to interview Dorrine and Jan Boelen.

JB: With the Trump administration issuing a ban on the immigration from certain Muslim-majority countries, like Sudan, can you tell us a little about your character of Joseph Malual, and his journey from Sudan to Iowa, and his role as a farmer and PhD student?

MS: Oh, Joseph is one of the most courageous men I know. Filled with integrity. He grew up in South Sudan and was baptized a Christian when he was thirteen. He was under threat of attack at all times during the war. He could be shot on the street at any time. So, he fled to the North, where he was oddly safer. He worked nights in a factory to get enough money to put himself through school. He finally was admitted to engineering school, but before he could complete his studies, he had to go off to serve in the army. He went to a training camp where he was pumped full of hate propaganda toward the U.S., France, and other countries. He fled the camp and started walking across Sudan. It took him three months and many traumas along the way to reach a refugee camp in Ethiopia. There, he tried to help the Lost Boys of Sudan and was thrown into prison for his work. He was confined for months under life-threatening conditions.

Finally, the U.N. intervened and he was evacuated from the refugee camp and flown to be settled in Des Moines. He arrived in Feb. in a jeans jacket. He was given enough money for one month’s food and lodging. He went to work in the meat packing plant in Des Moines, then saved his money, worked hard, and enrolled in the sustainable ag. program at ISU with an emphasis in sociology. His dream was to return home to create agricultural food learning centers in Sudan, but South Sudan is now more war torn than ever. He now has his PhD and is working with Wisconsin Extension Service.

He met his wife in Ethiopia. The couple went through years of paperwork to get her to the U.S. where they married and now have a family.

JB: What has been the reaction to the play in Iowa and elsewhere, and what has surprised you most in your talk-back sessions?

MS: Overall, Vang has been well-received. We’ve performed everywhere from farmers’ barns, to refugee centers, to the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.In the beginning when I was drafting the play, many of my writer friends were skeptical and cynical. “That’s great, Mary,” many of them said. “Where are you going to go to find the immigrants and refugees? California?” But that’s the point of the show. Immigrants and refugees are all around us. We’re not paying attention and not helping them much. They are providing a labor force and cultural strength for our country. Yes, there are problems, but these folks are working to solve their problems and some of ours, too. The Hispanic immigrants in Marshalltown, for example, are taking care of our veterans with their adopt a vet program. At the talk-backs after the shows, a certain percentage of the audiences are surprised to learn that not all immigrants are undocumented. When I heard that response, I realized we had to start with the basics, but that we were educating our audience. Vang is verbatim theatre, using the exact words of the interviewee—nothing made up.

JB: Much of your work features the role of narrative arts and storytelling in bringing together communities to discuss critical issues. How can communities like Iowa City learn from “Vang” to launch more storytelling projects in our towns, cities, counties and schools, especially to inform ourselves about shifts in demographics, migration, agriculture and food?

MS: Iowa City is a UNESCO City of Literature. We could bring all the talent that we have in this city to the forefront to create a model of narrative arts and storytelling to address critical issues. Kirkwood Community College is already taking the lead. They have applied for a major grant to have their international students interview the elderly in Iowa City. I can imagine a huge cultural exchange with this project. We could grow this initiative to include not only KCC students, but those in Journalism, Rhetoric, Theatre, Sociology, Geography, Anthropology, History, and other classes at the U. of Iowa. Iowa City high school students could also be involved. We could target a different issue every year. This initiative would not only educate audiences and bring more awareness to social justice issues, but it would improve communication skills of those involved.

Right now I’m involved in a food insecurity project in Storm Lake within the immigrant community there. These people are working in the meat packing plant, processing the food that most Americans eat, but the immigrants doing the hard work can’t afford to eat themselves. With the help of some of the churches in Storm Lake, we will be allowing the immigrant laborers to tell their own stories of food insecurity. We will present the stories at a major food insecurity conference in March.

JB: Any other thoughts?

MS: A couple of weeks ago we gave a Vang performance in Washington, Iowa for 200 people. Washington is a pretty typical rural county-seat town in Iowa. The town has a good share of immigrants working in the meat packing plants in neary-by Columbus Junction—again, a scenario that is more and more typical. Immigration is a hot topic, of course, in the U.S. right now, and Washington is generally on the right of the political spectrum. I felt the audience was actively engaged and thoughtful during the play and in their responses in the discussion. Several people complimented me afterwards on finding a way to open a civil discussion in a public forum about an issue that usually only sees polarization. “We so rarely see ourselves reflected in the arts like this,” one of the audience members told me.

In a week of turmoil over federal immigration and refugee travel orders, Iowa poet laureate Mary Swander’s nationally touring play, Vang: A Drama about Recent Immigrant Farmers, is opening a new door to the extraordinary stories of families from Sudan, Mexico, the Hmong in Laos, and Holland that are quietly rejuvenating the state’s aging agricultural communities.

Swander, author of several acclaimed works of poetry and memoir, as well as the plays, Farmscape, Driving the Body Back and Map of My Kingdom, based Vang on three years of interviews and research with New Iowans across the state. Swander teamed up with Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Dennis Chamberlin and Kennedy Center award-winning actor Matt Foss to bring the stories of their journeys and the challenges of transitioning to farm life in Iowa to stage in Vang—a Hmong word for “garden” or “farm.”

Iowa, of course, has always been a crossroads of immigration—and a host of refugees.

“The immigration to Iowa this season is immense,” noted an Iowa newspaper in 1855, “far exceeding the unprecedented immigration of last year, and only to be appreciated by one who travels through the country as we are doing, and finds the roads everywhere lined with movers.”

The movers in Vang and Iowa today include Joseph Malual, a refugee from Sudan, who managed to work and earn a PhD in Sustainable Agriculture from Iowa State University, as well as Hmong families who have become mainstays in the Des Moines farmer’s market, and newly arrived Dutch dairy farmers in Brooklyn, Iowa.

Theatre productions of Vang have been staged across the country, as well as in smaller communities in Iowa. Swander often holds talk-backs on immigrant stories in the changing farm towns.

“We so rarely see ourselves reflected in the arts like this,” one of the audience members recently told her.

In advance of a special staging of Vang at the historic Old Capitol Senate Chambers in Iowa City on Sunday, Feb. 12, as a kickoff for the Iowa Valley Global Food Project, I interviewed Swander on her latest work and its impact on audiences across the country.

JB: The story of Iowa, in many respects, has been the arrival of immigrants as farmers, who have carried on the state’s agricultural legacy. After the success of your play, Farmscape, how did you happen to pursue the stories of four immigrant families for your Vang play?

MS: I wrote Farmscape with a graduate class at Iowa State University. We wound the play together from interviews of farmers and others involved in the changing rural environment. The students in my class were diverse in terms of gender, ethnicity, cultural backgrounds,religions, urban/ rural backgrounds , geographical parts of the country and the world. I urged the students to go out and find diversity in their interviewees, yet when they actually hit the pavement the first time, most returned with interviews of white male farmers with common opinions and values. The students had internalized society’s stereotypes of farmers.

So we worked with the material and looked at our own biases. We went out into the field again and broadened our search, and eventually came up with a play that hit on some of the major issues in contemporary agriculture. The play began touring and the state folklorist saw it and liked it. Then she suggested that in the future I might explore recent immigrant farmers. A few weeks later a new faculty member in photo journalism—Dennis Chamberlin—walked into my office and said he’d like to work with me. His two loves: sustainable agriculture and immigrants. An idea was born.

Dennis and I spent 3 years researching Vang. We read and read about immigration, the experiences of different immigrant groups to the U.S. and the culture, values, and folklore of various countries. I worked to find the immigrant farmers, develop trust and rapport with the interviewees. I interviewed scores of immigrant farmers and secured translators. I narrowed down my scope to the four couples profiled in Vang. I went back to each set of farmers 3-10 times. Dennis and I always went together at first, then we would each return separately.

I started out interviewing Hmong farmers at the Des Moines farmers’ market. With the help of a Hmong lecturer at ISU who grew up in the Hmong community in Des Moines, I finally settled on Toua and A Vang. An ISU Mexican graduate student in sustainable agriculture helped me find Ramona and Beni in Marshalltown. Dennis had photographed Joseph Malual for another project. Joseph and I often sat near each other in a weekly seminar at ISU—but little did I know his story. I had heard a story on Iowa Public Radio about immigrant Dutch farmers and Pat Blank opened the door for me to interview Dorrine and Jan Boelen.

JB: With the Trump administration issuing a ban on the immigration from certain Muslim-majority countries, like Sudan, can you tell us a little about your character of Joseph Malual, and his journey from Sudan to Iowa, and his role as a farmer and PhD student?

MS: Oh, Joseph is one of the most courageous men I know. Filled with integrity. He grew up in South Sudan and was baptized a Christian when he was thirteen. He was under threat of attack at all times during the war. He could be shot on the street at any time. So, he fled to the North, where he was oddly safer. He worked nights in a factory to get enough money to put himself through school. He finally was admitted to engineering school, but before he could complete his studies, he had to go off to serve in the army. He went to a training camp where he was pumped full of hate propaganda toward the U.S., France, and other countries. He fled the camp and started walking across Sudan. It took him three months and many traumas along the way to reach a refugee camp in Ethiopia. There, he tried to help the Lost Boys of Sudan and was thrown into prison for his work. He was confined for months under life-threatening conditions.

Finally, the U.N. intervened and he was evacuated from the refugee camp and flown to be settled in Des Moines. He arrived in Feb. in a jeans jacket. He was given enough money for one month’s food and lodging. He went to work in the meat packing plant in Des Moines, then saved his money, worked hard, and enrolled in the sustainable ag. program at ISU with an emphasis in sociology. His dream was to return home to create agricultural food learning centers in Sudan, but South Sudan is now more war torn than ever. He now has his PhD and is working with Wisconsin Extension Service.

He met his wife in Ethiopia. The couple went through years of paperwork to get her to the U.S. where they married and now have a family.

JB: What has been the reaction to the play in Iowa and elsewhere, and what has surprised you most in your talk-back sessions?

MS: Overall, Vang has been well-received. We’ve performed everywhere from farmers’ barns, to refugee centers, to the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.In the beginning when I was drafting the play, many of my writer friends were skeptical and cynical. “That’s great, Mary,” many of them said. “Where are you going to go to find the immigrants and refugees? California?” But that’s the point of the show. Immigrants and refugees are all around us. We’re not paying attention and not helping them much. They are providing a labor force and cultural strength for our country. Yes, there are problems, but these folks are working to solve their problems and some of ours, too. The Hispanic immigrants in Marshalltown, for example, are taking care of our veterans with their adopt a vet program. At the talk-backs after the shows, a certain percentage of the audiences are surprised to learn that not all immigrants are undocumented. When I heard that response, I realized we had to start with the basics, but that we were educating our audience. Vang is verbatim theatre, using the exact words of the interviewee—nothing made up.

JB: Much of your work features the role of narrative arts and storytelling in bringing together communities to discuss critical issues. How can communities like Iowa City learn from “Vang” to launch more storytelling projects in our towns, cities, counties and schools, especially to inform ourselves about shifts in demographics, migration, agriculture and food?

MS: Iowa City is a UNESCO City of Literature. We could bring all the talent that we have in this city to the forefront to create a model of narrative arts and storytelling to address critical issues. Kirkwood Community College is already taking the lead. They have applied for a major grant to have their international students interview the elderly in Iowa City. I can imagine a huge cultural exchange with this project. We could grow this initiative to include not only KCC students, but those in Journalism, Rhetoric, Theatre, Sociology, Geography, Anthropology, History, and other classes at the U. of Iowa. Iowa City high school students could also be involved. We could target a different issue every year. This initiative would not only educate audiences and bring more awareness to social justice issues, but it would improve communication skills of those involved.

Right now I’m involved in a food insecurity project in Storm Lake within the immigrant community there. These people are working in the meat packing plant, processing the food that most Americans eat, but the immigrants doing the hard work can’t afford to eat themselves. With the help of some of the churches in Storm Lake, we will be allowing the immigrant laborers to tell their own stories of food insecurity. We will present the stories at a major food insecurity conference in March.

JB: Any other thoughts?

MS: A couple of weeks ago we gave a Vang performance in Washington, Iowa for 200 people. Washington is a pretty typical rural county-seat town in Iowa. The town has a good share of immigrants working in the meat packing plants in neary-by Columbus Junction—again, a scenario that is more and more typical. Immigration is a hot topic, of course, in the U.S. right now, and Washington is generally on the right of the political spectrum. I felt the audience was actively engaged and thoughtful during the play and in their responses in the discussion. Several people complimented me afterwards on finding a way to open a civil discussion in a public forum about an issue that usually only sees polarization. “We so rarely see ourselves reflected in the arts like this,” one of the audience members told me.