Sociologists have discovered a surprising fact. When a group of people are in an unfenced space, no matter how large, they gravitate towards the outskirts and leave the middle empty. On the other hand, in a fenced space, they will spread out and enjoy the use of the whole area. Maybe this truth helps explain the charm of courtyards, and the fact that the etymology of the word “paradise” is simply “a walled enclosure.” It may also help explain the lasting appeal of the sonnet, the form that Rita Dove has called a “little world.”

Did I say lasting appeal? Doesn’t everyone know that the sonnet should be dead by now? As the poet Tim Yu put it in his blog last year, “the real issue, to my mind, in using a form like the sonnet is belatedness.” Doesn’t it go without saying that the sonnet is a form too late for itself, too old-fashioned to really exist? Somehow, though, the sonnet has not cooperated with the reports of its death. People keep writing them. This essay will explore why, and how, and along the way, investigate a new model of how poetry works through time that might modify somewhat the twentieth-century adhesion to “progress.”

“A sonnet is a moment’s monument, / memorial to one dead deathless hour,” wrote Dante Gabriel Rossetti in one of the most famous sonnets on the sonnet (as you might expect, no other form has inspired nearly as many tributes to itself). Rossetti expresses one of the most useful powers of the sonnet: the ability to keep a moment, to hold a feeling or experience and turn it around in the light of our awareness until many facets are evident. This multifaceted quality gives the sonnet a paradoxical feeling of freedom and expanse within confines:

“Nuns Fret Not,” William Wordsworth (1807)

Nuns fret not at their convents’ narrow room;

And hermits are contented with their cells;

And students with their pensive citadels;

Maids at the wheel, the weaver at his loom,

Sit blithe and happy; bees that soar for bloom,

High as the highest Peak of Furness-fells,

Will murmur by the hour in foxglove bells:

In truth the prison, into which we doom

Ourselves, no prison is: and hence for me,

In sundry moods, ’twas pastime to be bound

Within the Sonnet’s scanty plot of ground;

Pleased if some Souls (for such there needs must be)

Who have felt the weight of too much liberty,

should find brief solace there, as I have found.

Here Wordsworth uses both the iambic pentameter and the sonnet form to illustrate the paradox of what Emerson called the “restraints that make us free.” I recently saw the deep, embracing blossoms of purple foxgloves for the first time in a friend’s garden; I now understand even better the sensual pleasure, wonder, and calmness that Wordsworth, who wrote 500 sonnets, was describing here. For me also, the feeling of starting a sonnet can carry a sense of mingled freedom, comfort and curious excitement that is different from starting any other kind of poem.

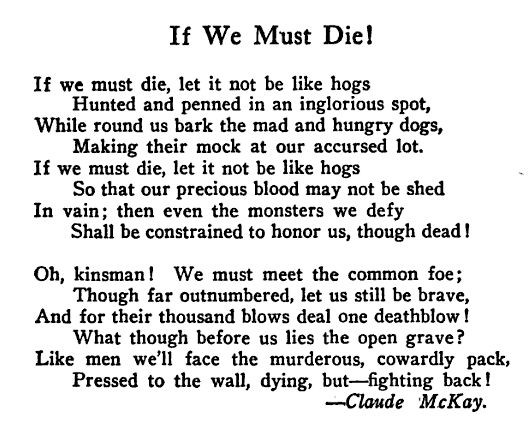

The quality of exploring all facets of a subject does not mean sonnets are always calm; it also means they are able to carry the full force of a lyric outburst with complete conviction. This authority gave Claude McKay’s sonnet “If We Must Die,” written in prison in 1919, an urgency so powerful that eventually it became a talisman in the civil rights struggle:

“If We Must Die,” Claude McKay (1919)

If we must die — let it not be like hogs

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot,

While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs,

Making their mock at our accursed lot.

If we must die — oh, let us nobly die,

So that our precious blood may not be shed

In vain; then even the monsters we defy

Shall be constrained to honor us though dead!

Oh, Kinsmen! We must meet the common foe;

Though far outnumbered, let us show us brave,

And for their thousand blows deal one deathblow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

While the sentiments are powerful, the imagery strong, and the art skillful, I don’t think any of these accounts for the impact that McKay’s sonnet had on so many people. While all these play a part in the poem’s effect, I give the most credit to how well McKay understood and worked with the sonnet form itself. The first two quatrains have a somber tone, a heaviness emphasized by the repeating phrase “if we must die,” with its sonorous spondee. But at the beginning of line 9, with the phrase “Oh, Kinsmen!,” McKay’s sonnet seems to stop, take a deep breath, and regather its energies for a big push to the finish.

The ninth line of either the Italian or the English sonnet form is called the “volta,” the Italian word for “turn.” At this point, the sonnet form is designed to change from one idea, tone, or approach in the octave to a different idea, tone or approach in the sestet. And, just as the secret of success in poetry may be to make full use of what you find most unique and distinctive about poetry, the secret to success with any poetic form may be making full use of whatever is most unique and distinctive about the form. Skillful sonnets usually take good advantage of the volta, the most unique and distinctive aspect of a sonnet.

In McKay’s volta, many factors, including syntax, meter, trope, word-music, and connotation as well as meaning, conspire to make the turn as effective as it is. Take the word “must,” for example. If you read aloud the lines containing this word at the beginnings of the first two quatrains, you will hear something between resigned bitterness and sad determination conveyed by the spondaic stress on the first “must,” and a firmer, mounting determination in the second “must.” But after the volta, the same word has changed its intensity entirely, the spondee conveying an unstoppable force that floods over the expected unstressed syllable in irresistible exhortation.

Word-music plays a part in the change as well. The three “m”s in “men,” “must,” and “meet” gather together to surpass and overwhelm the previous “m”s in “making their mock” and “monsters.” It is also significant that one of these “m” sounds happens in the syllable “men,” contrasting “men” with the simile of “hogs” that opened the poem, and setting the stage for the transformation that will happen by the end of the poem, where the African American prisoners will have become “men” while their oppressors still remain a “pack” of dogs. The phrase “Oh, kinsmen!” right at the volta is the heart of the sonnet not only because it brings in the word “men,” but also because it does so through the word “kinsmen,” emphasizing that it is only in their sense of brotherhood that the prisoners will find the strength they need to prevail.

Reading the poem aloud, you may notice that your energy level and pulse-rate rise after line 9. I think the most significant reason for this change is metrical. With the word “kinsmen,” the poem begins to take on more trochaic feel: “We must meet the common foe” sounds exactly like a footless trochaic line, and phrases such as “far outnumbered” continue the powerful rocking trochaic rhythm, in contrast to the doggedly iambic feeling of the octave, where the only trochaic words (“hunted” and “making”) are dutifully combined to their traditional and most impotent place in the first foot of the line. The trochaic undercurrent of this poem is no surprise in the context of African American poetics; the trochaic meter has been used by African American poets as a powerful alternative to iambic meter in such poems as Countee Cullen’s “Heritage” and Gwendolyn Brooks’ “The Anniad.”

It’s hard to imagine “If We Must Die” in another kind of poetic form — a ballad, or quatrains, or free verse. Who would have thought the sonnet, known so well as the vehicle for plaintive or poignant poems of love, would also prove the perfect vehicle for McKay’s revolutionary call: at once big and loose enough for the pacing and circling of authentic power, and small and structured enough for the channeling and building of directed force? How can a poetic form be so versatile? We might as well ask, though, how can a human voice be so versatile? Something in the shape of the sonnet seems so well suited to convey human feeling that it can feel almost like a throat, a hand, a voice — and yes, also like a stanza or room that is especially well-proportioned to suit the human form.

And, as it turns out, there is truth behind this idea of the connection between the sonnet and the human body. Almost all traditionally-formed sonnets have 14 lines and consist of an octave (8 lines) and a sestet (6 lines) with that significant shift in emphasis, the volta or turn, between them. The critic Paul Oppenheimer has observed that since the last two lines of a sonnet are often separated off from the rest in a couplet or an implied couplet that closes the poem, the proportions of the form are 6:8:12. And this proportion, in fact, represents the special mathematical ratio which the Greeks called the Golden Mean.

A ratio found throughout nature, the Golden Mean is apparent in the proportions by which flower petals grow, twigs sprout from stems, and the shapes of snowflakes crystallize. It is also a ratio evident in the proportions of the human body. Oppenheimer feels that this compelling ratio is one of the reasons for the sonnet’s lasting power, which has brought it into numerous languages and which made it part of the vocabulary of virtually every major poet in Italian, German, French, Spanish, and English over seven centuries.

In fact, the sonnet is the ultimate stanza, an enclosed place of words alive with currents of energy and places to rest. It has provided a place for some of the most intense and memorable lines in English-language poetry to come into being: “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways . . . Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers . . . That time of year thou mayst in me behold . . . Euclid alone has looked on Beauty bare . . . Oh mother, mother, where is happiness . . . one day I wrote her name upon the strand . . . A sudden blow, the great wings beating still . . . When I have fears that I may cease to be . . . Fool, said my muse to me, look in thy heart and write.”

The Italian or Petrarchan sonnet is the strictest form, with only two rhyming sounds in the octave and three in the sestet. This economy of rhyme sounds can bring great beauty, so the form sounds like the inhale and exhale of a breath. This two-part structure lends power to the volta, which we have seen can structure the thought process in ways from the obvious (“In truth, the prison. . .”) to the more subtle:

“Unholy Sonnet,” Mark Jarman

After the praying, after the hymn-singing,

After the sermon’s trenchant commentary

On the world’s ills, which make ours secondary,

After communion, after the hand wringing,

And after peace descends upon us, bringing

Our eyes up to regard the sanctuary

And how the light swords through it, and how, scary

In their sheer numbers, motes of dust ride, clinging —

There is, as doctors say about some pain,

Discomfort knowing that despite your prayers,

Your listening and rejoicing, your small part

In this communal stab at coming clean,

There is one stubborn remnant of your cares

Intact. There is still murder in your heart.

This poem, where the worshiper tries to integrate repressed feelings into a pious character, serves as a good illustration for Oppenheimer’s idea of the sonnet as the container for the personality’s complexity (see below). The smooth and almost imperceptible transition of the volta perhaps underscores the difficulty the speaker has at first in consciously accepting the hidden thoughts.

This caustic narrative sonnet uses the volta to create a change of scene:

“Sonnet 115,” John Berryman (1947)

All we were going strong last night this time,

the mosts were flying & the frozen daiquiris

were downing, supine on the floor lay Lise

listening to Schubert grievous & sublime,

my head was frantic with a following rime:

it was a good evening, and evening to please,

I kissed her in the kitchen — ecstasies —

among so much good we tamped down the crime.

The weather’s changing. This morning was cold,

as I made for the grove, without expectation,

some hundred Sonnets in my pocket, old,

to read her if she came. Presently the sun

yellowed the pines & my lady came not

in blue jeans & a sweater. I sat down & wrote.

Edna St. Vincent Millay, one of the most noted writers of sonnets in the twentieth century and called by Edmund Wilson the successor to Shakespeare, frequently favored the Italian form. Some say the Italian form is harder to write in English than the English form, since it needs more rhymes for each sound; but in Millay’s hands the rhymes rarely sound forced. Here is her contribution to the genre of the sonnet about writing a sonnet:

“I will put Chaos into fourteen lines,” Edna St. Vincent Millay (c. 1945)

I will put Chaos into fourteen lines

And keep him there; and let him thence escape

If he be lucky; let him twist, and ape

Flood, fire, and demon — his adroit designs

Will strain to nothing in the strict confines

Of this sweet Order, where, in pious rape,

I hold his essence and amorphous shape,

Till he with Order mingles and combines.

Past are the hours, the years, of our duress,

His arrogance, our awful servitude:

I have him. He is nothing more nor less

Than something simple yet not understood;

I shall not even force him to confess;

Or answer. I will only make him good.

The Italian sonnet’s lack of a closing couplet and greater balance between octave and sestet doesn’t mean it can’t be used to great rhetorical force. The combination of energy and containment, development and resting, that structures “If We Must Die” is part of the quality that helped make Emma Lazarus’ sonnet for the Statue of Liberty so durable and beloved:

“The New Colossus,” Emma Lazarus (1883)

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame,

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore,

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

While the first line and a half after the volta is somewhat thrown away, Lazarus more than makes up for it in the last four lines of the sestet, which can stand as a quatrain on their own, and which carry in four lines all the accumulated force that McKay disperses throughout his sestet. So, while “The New Colossus” may not fully embody the potential of the sonnet as a sonnet, it is still a reflection of the rhetorical power of the form.

The English or Shakespearean sonnet, adapted from the Petrarchan model by Sir Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey and Sir Thomas Wyatt, and perfected by Shakespeare, has a more logically complex shape than the Italian, with a pattern of 4–4–4–2 lines:

“Sonnet II,” William Shakespeare

When I do count the clock that tells the time,

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night,

When I behold the violet past prime,

And sable curls all silvered o’er with white:

When lofty trees I see barren of leaves,

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd

And summer’s green all girded up in sheaves

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard:

Then of thy beauty do I question make

That thou among the wastes of time must go,

Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake,

And die as fast as they see others grow,

And nothing ‘gainst Time’s scythe can make defence

Save breed to brave him, when he takes thee hence.

Like Mckay’s English sonnet, this one uses the first quatrain to establish an idea and the second to build on it in a different but related way. Whereas McKay’s volta introduced a new emotional tone, in this sonnet, as in most of Shakespeare’s line 9, the volta brings in a new idea or logical approach: the idea of the lover — and a new attitude of questioning insecurity. The final couplet, like the final couplet of “If We Must Die,” sums up the problem and offers a solution — in this case to produce “breed,” creative or actual progeny.

The English sonnet’s closing couplet, and the great logical potential of its structure, doesn’t mean it can’t be used for a poem with a delicate balance between octave and sestet. This remarkable sonnet about balance has always seemed to me not only like a love poem but also like a tribute to the sonnet form itself:

“The Silken Tent,” Robert Frost

She is as in a field a silken tent

At midday when the sunny summer breeze

Has dried the dew and all its ropes relent,

So that in guys it gently sways at ease,

And its supporting central cedar pole,

That is its pinnacle to heavenward

And signifies the sureness of the soul,

Seems to owe naught to any single cord,

But strictly held by none, is loosely bound

By countless silken ties of love and thought

To every thing on earth the compass round,

And only by one’s going slightly taut

In the capriciousness of summer air\

Is of the slightest bondage made aware.

There is a very unusual secret in this sonnet. Read it through carefully and see if you can find what it is (hint: it has something to do with punctuation).

Whether in the Italian or English form, the sonnet allows for dialectical opposition, tension and resolution within one stanza; it can unite opposing attitudes within one identity. Paul Oppenheimer makes a convincing argument that because the sonnet allowed room to struggle with oneself, it marks not only the beginning of modern poetry but the beginning of the modern idea of our “self” as having a complex internal life. If this is so, then the sonnet form is likely to continue to be useful at least as long as we encourage such feelings of interiority; and the current resurgence of sonnets suggests that the form can help express the decentered contemporary “self” as well.

Never static, the form of the sonnet has mutated numerous times since its invention by a lawyer in 12th-century Italy, based on an old folk song stanza. Milton and Spenser each invented new sonnets that are named after them, and Shakespeare and Petrarch built such durable versions of the form in their respective languages that the two major forms of sonnet took their names.

Until the twentieth century, the major variations in the sonnet were “formal” variations that preserved the basic qualities of the form. The Miltonic sonnet is a Petrarchan sonnet without the volta. The Spenserian sonnet has an innovative overlapping rhyme scheme but still keeps the couplet separate: a b a b b c b c c d c d e e. Gerard Manly Hopkins’ “curtal sonnet” uses the same proportions but makes them smaller, so instead of 8 and 6 lines, the two parts are 6 and 4 ½ lines in length:

“Pied Beauty,” Gerard Manly Hopkins (1877)

Glory be to God for dappled things

For skies of couple color as a brindled cow;

For rosemoles all in stipple upon trout that swim

Fresh firecoal chestnut falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced

Fold, fallow and trim.

Glory be to God for dappled things

All things counter, original, spare, strange;\

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)\

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim

He fathers forth whose beauty is past change;

Praise him.

Gwendolyn Brooks’ mid-twentieth experiment maintained the sonnet’s formal structure, but changed the feeling of the form:

“The Sonnet-Ballad,” Gwendolyn Brooks (1949)

Oh mother, mother, where is happiness?

They took my lover’s tallness off to war,

Left me lamenting. Now I cannot guess

What I can use an empty heart-cup for.

He won’t be coming back here any more.

Some day the war will end, but, oh, I knew

When he went walking grandly out that door

That my sweet love would have to be untrue.

Would have to be untrue. Would have to court

Coquettish death, whose impudent and strange

Possessive arms and beauty (of a sort)

Can make a hard man hesitate — and change.

And he will be the one to stammer, “Yes.”

Oh mother, mother, where is happiness?

While Brooks maintains the form of an English sonnet, the dialogue, the directly emotional voice of the girl, the simple and universal narrative, and the repetition of the first line, like a refrain, add the immediacy and narrative urgency of a ballad. Hers is such a unique variation that it bears its form as a title, but other variations are more common. Here is a partial list of sonnet variations, a cross-section of a constantly expanding vocabulary of shapes and permutations:

- Caudate (tail) sonnet: a sonnet of any type, followed by an extra couplet (or sometimes an extra trimeter, followed by a heroic couplet, followed by a trimeter rhymed with the first, followed by another heroic couplet.)

- Chained or linked sonnet: each line starts with last word of previous line

- Continuous or reiterating sonnet: uses only one or two rhymes in the entire sonnet

- Crown of sonnets: a sequence of sonnets, each of which begins with the last line of the previous sonnet

- Interwoven sonnet: includes both medial and end rhyme

- Miltonic sonnet: an Italian sonnet with no break in sense at the volta, creating a gradual culmination of the idea

- Retrograde sonnet: reads the same backwards as forwards

When I was in my 20s, partly out of poetic curiosity, partly for feminist reasons, and partly out of a desire to help reestablish form with a difference in the postmodern age, I set out to invent my own sonnet. Based on many such experiments, here are my personal minimum criteria for a variation so that I still feel the connection to the form’s roots: the poem keeps some kind of consistent meter, though not necessarily iambic pentameter; the poem has some kind of meaning-dynamic between different parts, analogous to the volta; the poem’s length and proportions, like the sonnet’s, feel similar to the palm of my hand; and every line in the poem has at least one rhyming partner, to keep the vital propulsive force of the form. Twenty years later, I was finally given the idea for my own version of the sonnet by a figure from a dream. It’s a much more radical departure than I could have imagined in my 20’s: a nine-line poem in dactylic tetrameter with the form abcbcbaca, which I call the “nonnet.” It’s taken me yet another decade of organic, tentative, tactful experiment, pushing at my own boundaries, to begin to feel familiar with writing nonnets, and I don’t know yet if my form has any “legs.” If it turned out that it did, I would be honored to be in the company of numerous other poets, famous and obscure, from all centuries, who have developed their own forms based on the sonnet.

The most common contemporary formal variations of the sonnet include such permutations as unrhymed metrical sonnets of 14 lines with a volta; rhymed nonmetrical (free verse) sonnets; sonnets that are metrically variable (avoiding a consistent meter); and sonnets of various lengths (including 16, 18, and 12 lines) that keep rhyme and meter. When the influential poet Robert Lowell published three books of unrhymed sonnets in the 1960s and 70s, most were dense iambic pentameter:

“History,” Robert Lowell

History has to live with what was here,

clutching and close to fumbling all we had —

it is so dull and gruesome how we die,

unlike writing, life never finishes.

Abel was finished; death is not remote,

a flash-in-the-pan electrifies the skeptic,

his cows crowding like skulls against high-voltage wire,

his baby crying all night like a new machine.

As in our Bibles, white-faced, predatory,

the beautiful, mist-drunken hunter’s moon ascends —

a child could give it a face: two holes, two holes,

my eyes, my mouth, between them a skull’s no-nose —

O there’s a terrifying innocence in my face

drenched with the silver salvage of the mornfrost.

Lowell’s unrhymed sonnet follows strictly the rhetorical shape of the English sonnet, with each quatrain having its own subject, a dramatic change of mood at the volta, and a concluding couplet that steps back from the poem to take a wider view.

Informal sonnet variations (or “deformations,” as Michael Boughn has proposed calling them in recognition of their subversive attitude towards the form), jettison meter as well, basically keeping nothing but the name “sonnet,” though they may be 14 lines and/or may have a volta. The most central writers of this kind of sonnet are Ted Berrigan and Bernadette Mayer. As an example of informal variation, here is a poem from Berrigan’s first book Sonnets (1964), for which he took fragments of poems written earlier and collaged them into an approximate sonnet shape:

In Joe Brainard’s collage its white arrow

he is not in it, the hungry dead doctor.

Or Marilyn Monroe, her white teeth white —

I am truly horribly upset because Marilyn

and ate King Korn popcorn,” he wrote in his

of glass in Joe Brainard’s collage

Doctor, but they say “I LOVE YOU”

and the sonnet is not dead.

takes the eyes away from the gray words,

Diary. The black heart beside the fifteen pieces

Monroe died, so I went to a matinee B-movie

washed by Joe’s throbbing hands. “Today

What is in it is sixteen ripped pictures

does not point to William Carlos Williams.

While there is no regular meter or rhyme, the poem has 14 lines and, significantly, the line “and the sonnet is not dead” is not only in regular meter (trochaic tetrameter, or headless iambic tetrameter, depending how much one privileges the iambic meter), but appears resoundingly at the end of the octave, constituting a volta. This tradition of playful or subversive deformation of the form has continued, largely through the influence of Mayer’s book Sonnets, consisting of free verse poems of different lengths that usually preserve a volta or turn about halfway through. Some more recent examples that preserve only one formal aspect of the traditional sonnet are Lee Ann Brown’s “Quantum Sonnet,” consisting of disjointed phrases of free verse rhymed according to the Shakespearean pattern, and Terrance Hayes’ poem “Sonnet,” consisting of the same iambic pentameter line (“We sliced the watermelon into smiles”) repeated 14 times. Other deformations take the form more loosely still, sometimes treating it as a conceptual framework only. Jen Bervin’s book Nets, for example, uses tracing paper to cross out certain words in sonnets by Shakespeare to create a palimpsest series of “sonnets.” A remarkable range of other experiments with the idea and the body of the sonnet are collected in the recent British anthology The Reality Street Book of Sonnets.

Poet David Cappella has coined the terms endoskeleton and exoskeleton for the two basic approaches to varying the sonnet. I find Cappella’s categories extremely useful because they are descriptive rather than judging in one direction or the other. As he has explained, “some sonnets use the sonnet form as an endoskeleton — those are the poems that are actually written according to the sonnet form. But my poems use the form as an exoskeleton. I think of the sonnet form as a hard skeleton that exists outside and beyond my poems. My poems assume that the sonnet exoskeleton exists and play off of it, inhabit it, even though they are not structured internally according to the form.”

One of the most interesting aspects of the sonnet’s recent history is that there seems to be a trend now away from informal deformations or exoskeletons, and back to the strictest and most conservative form of the sonnet. Karen Volkman’s recent collection of extremely experimental iambic pentameter sonnets does not experiment at all with the most traditional aspects of the form — not even with meter:

“Sonnet,” Karen Volkman

Say sad. Say sun’s a semblance of a bled

blanched intransigence, collecting rue

in ray-stains. Smirching pages. Takes its cue

from sateless stamens, flanging. Florid head

got no worries, waitless. Say you do. Say

photosynthesis. Light, water, airy bread.

What eats its source, its orbit? Something bad:

some plural petal that will not root or ray.

Sow stray. Salt night for saving, dreaming clay

for heap, for hefting. Originary ash

for stall and stilling. Say it will, it said.

Corolla corona, bliss-bane — delay

surge and sediment. Say instrument and gash

and ruminant remnant. Rex the ruse. Be dead.

Nor is Volkman the only contemporary poet with roots in the post-avant-garde who seems to be, to some extent at least, questioning the 100-year-old idea that conventional form is old-fashioned and free verse is new, focusing instead on challenges to conventional meaning and syntax.

The sonnet has already risen from the dead once. It suffered over a hundred years of silence during the reign of the heroic couplet. Only a short few decades before the sonnets of Wordsworth and Keats, Samuel Johnson wrote in his authoritative Dictionary, “[the Sonnet] is not very suited to the English Language, and has not been used by anyone of eminence since Milton” — thus giving eternal hope to any poet who feels drawn to an unpopular form or style of writing.

Now, the sonnet may be rising from the dead again. Could it be that further great changes for the sonnet are in store? Or could it be that western poetry is finally building a sustainable tradition, a vocabulary of kinds of formal and free poetry that will last, as the ghazal has lasted for millennia in India and the Arabic world? The very familiarity of the sonnet expands a poet’s possibilities for working with and changing it, and, on exploration, the apparently confining poetic structure of this stubbornly persisting form may prove one of the most accommodating poetic shapes.

Note: This essay was adapted from A Poet’s Craft: A Comprehensive Guide to Making and Sharing Your Poetry (University of Michigan Press).