Okay, who’s ready for a little poetry? Did I say ‘a little’? I meant plenty of good poetry to go around.

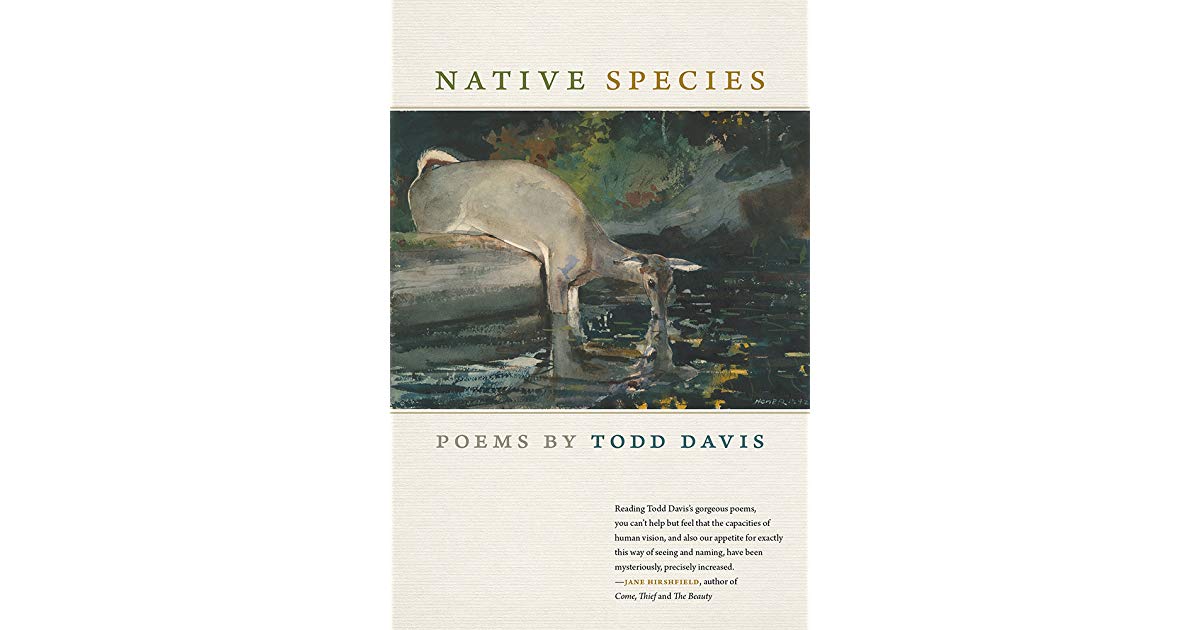

To begin, in search of the divine in the daily, the selections in “Native Species” from Todd Davis, professor of environmental studies and creative writing at Penn State University get to the heart of what matters.

His “Almanac of Faithful Negotiations,” for example, reveals the “evidence of elk, but not the elk themselves,” before the “susuration of/ wind, stars moving back into the invisible, all of us wondering when we/ will join them.”

Davis’s lines tend toward this divide, the observable world just next to the imagined or the wondered about, his relics marooned in mud as well as in the flood of unstoppable time.

The tight turns in “17-Year Locust” have the poet wondering in miniature about whether the brief metamorphosis of the insect has them calling “out for the sun/ they’ve never seen” or crying “a lament for the darkness/ abandoned in the husks/ they cannot retrieve?”

This palpable tension between lost and found is perhaps best exemplified in the title poem. Spending time at work looking at online images of deer, the man in question, before long, “began to suspect something.” Suspicion soon turns to the place “where his back bent and lengthened,/ neck drawn out, eyes brought to the side, dusky and knowing.”

This transformation is complete when his family can look from the window “on velvet antlers,/ illuminated like branches in the snow.”

U.S Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith is also back, with “Wade in the Water,” her lines composed in the shadow of slavery, as well as other spaces between the historical and the quotidian. In “Unwritten,” for example,, Smith writes in the voice of slaveholders, “(The loss of a servant is great),/ But for our own good we have to answer/ For all that has happened. Please. All.”

These final syllables carry centuries painful echo.

Later, in “”Charity,” the pace is slower, as we read, “She is like a squat old machine,/ Off-kilter but still chugging along/ The uphill stretch of sidewalk/ On Harrison Street, handbag slung/ Crosswise and, I’m guessing , heavy.”

Smith’s verse indeed shoulders heavy emotional weight, though she, thankfully, avoids didactic tendencies.

There is more too, as Michigan poet Jack Ridl’s new book “Saint Peter and the Goldfinch” features keen observations of simple human transactions, such as in “The Week After” where a divorced father meets again his two young sons, and though they are “eight and seven…He will read to them tonight/ for the first time.”

In “Nearing November” the narrator observes “an old radio, a table covered with/ maps” as the “lamp tilts away/ from the window,” the moment leading him to “think star, the infinite/ riff of atom, the endless solo of form.” Ridl’s poems riff from simple as well as suggestive.

He moves too in other neighborhoods close to home, as in his “Suite for the Long Married,” as he explains, “The bins of wants are full, and yet/ we want to want, and so we go,” though too “No longer needing/ a reason to live, we let ourselves be.”

Close to home, deep in the north woods, or threaded historical fabric, the poems in these collections remind readers of how a little poetry can provoke, salve, or calm as needed.

Good reading.