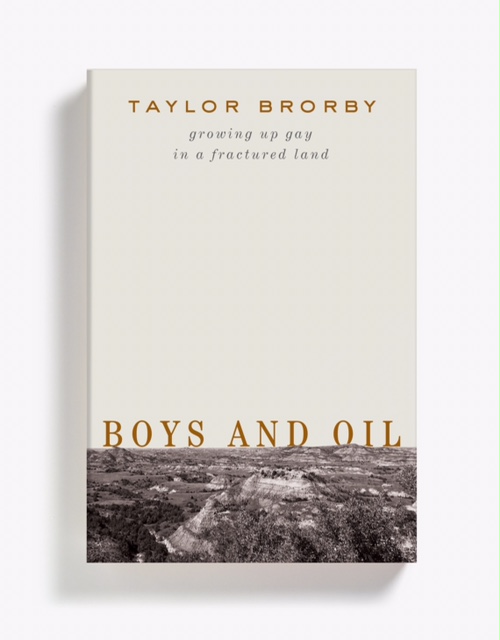

BEI Emeritus Fellow Taylor Brorby’s newest book is releasing this June! Now is the perfect time to pick up an early copy of this book that is sure to be phenomenal. To preorder, click the link here.

About the Book

From a young, gay environmentalist, a searing coming-of-age memoir set against the arid landscape of rural North Dakota, where homosexuality “seems akin to a ticking bomb.”

“I am a child of the American West, a landscape so rich and wide that my culture trembles with terror before its power.” So begins Taylor Brorby’s Boys and Oil, a haunting, bracingly honest memoir about growing up gay amidst the harshness of rural North Dakota, “a place where there is no safety in a ravaged landscape of mining and fracking.”

In visceral prose, Brorby recounts his upbringing in the coalfields; his adolescent infatuation with books; and how he felt intrinsically different from other boys. Now an environmentalist, Brorby uses the destruction of large swathes of the West as a metaphor for the terror he experienced as a youth. From an assault outside a bar in an oil boom town to a furtive romance, and from his awakening as an activist to his arrest at the Dakota Access Pipeline, Boys and Oil provides a startling portrait of an America that persists despite well-intentioned legal protections.

Review from Kirkus Reviews

Searching memoir of growing up gay in an uncomprehending place and family.

“Center is a place where people only end up,” writes poet and essayist Brorby. That little town—aptly named in standing nearly at the center of North Dakota, which in turn is nearly in the center of North America—is a place of taciturn farmers and bored teenagers, some of the latter of whom wind up dead, commemorated by roadside crosses “if they were nice.” Now a writer and environmental activist, Brorby was bookish and not terribly sports-minded, marking him for bullying, though he took to fly-fishing early on and loved the outdoors. “My classmates played video games,” he writes, “worked on the family ranch, and didn’t escape to the musical world of western meadowlarks and ring-necked pheasants.” Leaving Center for high school in the state capital and college and graduate school out of state provided an escape. All the while, the young author wrestled with identity and thoughts of suicide until landing on the answer that he would struggle to bring to his family: “I am gay—the shortest, most life-changing sentence a person can say. But it wasn’t really being seen by someone else that confirmed my gayness, it was my self-knowledge.” It was also, he learned, something his sister had long known and his grandparents readily accepted, though it was more difficult to negotiate a path to acceptance with his mother and father. In elegant chapters that often form stand-alone essays, we see Brorby easing into his own skin, acknowledging both the beauty and rough edges of his rural upbringing, and discovering that he is far from alone (he describes one small town as, perhaps improbably, “a gay Mecca”). In the end, he writes, “I no longer feel ashamed for the person I am,” a realization hard won over the course of a well-crafted narrative.

A closely observed account of both landscape and self.