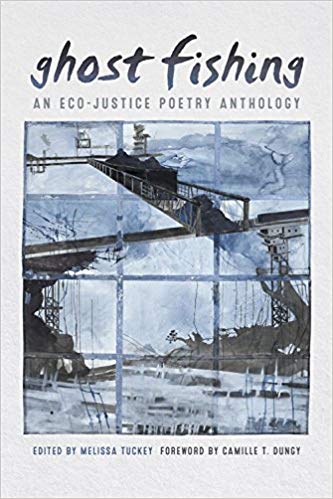

Melissa Tuckey, BEI Emeritus Fellow and co-editor of About Place Journal, recently was featured talking about her book Ghost Fishing: Eco-Justice Poetry Anthology with co-author Camille Dungy. For the original link to the article.

Copies of Ghost Fishing can be purchased here.

Poets are scribbling and keyboarding away, asking justice for people and the planet. Such work has a new name, eco-justice poetry, as celebrated in Ghost Fishing: An Eco-Justice Poetry Anthology.However, poems celebrating humans’ relationship to the land, and decrying how the most impoverished suffer along with the environment, have been around for decades, although often under the radar. Eco-justice poetry has also been outside the mainstream in part because it celebrates a variety of voices, diverse perspectives on the animals and plants that surround and sustain us.

“An eco-justice poem is an environmentally engaged poem that takes into account the realities of the human impact on the wider world,” writer and professor Camille Dungy told me. Indeed, Dungy’s earlier volume, Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry

, was a precursor to the themes found in Ghost Fishing.

Dungy expands on this new/old form, explaining that to “add the word justice” to environmental poetry, “means that the observing eye is also paying attention to questions of parity, of injustice and inequality.” Eco-justice poetry, then, includes poems of celebration and, perhaps even more given our realities, of protest.

To get to eco-justice poetry meant challenging some assumptions of the traditional environmental movement, mostly led by white, affluent people, often men. “To pretend that there’s one universal voice . . . that’s going to speak for all of the people on the environment, that is a problem,” said poet Melissa Tuckey, editor of Ghost Fishing. “It erases all of those different ways of telling and knowing, and all of those different languages and stories and histories.”

Dungy, who dates the contemporary definition of eco-justice poetry to 2005, when concepts of nature poetry began to expand, agrees that the form would not exist without a multicultural array of poets. To her, the poetry means “that a lot more voices get heard, and related, that a lot more voices can begin to make actual, substantive, necessary change in world.”

Ghost Fishing aims to do its small part in healing a world divided by race and nation that, not coincidentally, faces an environmental cliff that is wiping out massive numbers of species and making our planet unfit for human habitation. This means tending to neglected traditions. Thus, alongside the extreme contemporary, Ghost Fishing includes poems from the past hundred years or so.

Many of the anthology’s poems at one point would not have been considered “environmental.” So Dungy includes a poem on a “canning ritual that people have done for generations to help preserve food and prevent food scarcity and to survive on land.” Such a work, about our desperate and nurturing relationship to the land, does not come out of nowhere. One precursor, Lucille Clifton, writes about gardens, how a relationship with nature helped African Americans survive, in her 1987 poem on cutting greens:

curling them around

i hold their bodies in obscene embrace . . . .

collards and kale

strain against each strange other . . . .

and i taste in my natural appetite

the bond of living things everywhere

Whether we know it or not, we are all part of an erotic dance with nature (these days, too often a distant, impersonal dance). Tradition, filtered through the poetic voice, helps people reconnect to the land we have too often left behind.

Of course, too often humans are ravaging land, not just in the United States but around the world. And often it’s the poor and dispossessed who endure the hard daily labor of exploiting nature. Wang Ping writes in “A Hakka Man Farms Rare Earth in South China” of drudgery and labor in the mud. She implies a lost glory: “Mongolia / Our origin, now a rare earth pit for the world.” In this once proud corner of the planet, the man grieves for his wife, poisoned by the minerals he digs up:

Fire licks my wife’s slender hands

and fumes in her lungs, liver, stomach

Till she can no longer sip porridge laced

With the thousand-year-old egg

This is only one version of an old story. From rural North Carolina—where the environmental justice movement began—to India’s Bhopal gas disaster, to hurricanes ravaging the U.S. Gulf Coast, to lead poisoning in Zambia, it’s the poor and minority groups who have paid the largest price for the shiny products enjoyed by the affluent. Thus, uranium mining in the Navajo nation likely led to recurring kidney failure and cancer. Today’s environmental justice movement has only come about after a long period of voicelessness.

Ignoring numerous peoples, especially indigenous people, has meant neglecting the voices of environmental stewards who have lived as part of the land for millennia. The environmental movement can only be strengthened by listening to these voices. “Absolutely, indigenous Americans have had a different narrative with their understanding of the land,” said Dungy. “Our American wilderness aesthetic . . . erases people who have been living on that land. Yosemite and Yellowstone—the creation of both of those parks meant the removal of people who had made those spaces their homes for tens of thousands of years.” Twentieth-century environmentalists often demanded a separation of nature from people as “preservation.” Yet now at least some of those voices are beginning to speak up.

Given our current crisis, and the thundering voices of reaction, this reawakening is overdue. Increasingly, environmental poetry means a desperate celebration of what is rapidly disappearing. Thus, the poet Jennifer Elise Foerster remembers her own history conjoined with a more ancient one:

Once there were coyotes, cardinals

in the cedar. You could cure amnesia

In the trees of our back-forty. Once

I drowned in a monsoon of frogs

All of us who visit nature—or keep abreast of the latest studies—know that it is becoming quieter, more fragmented, less dense with species. Environmental poetry is increasingly becoming an elegy for a world slipping away.

The crisis is both human and environmental. Still, Tuckey sees poetry as one means of healing a divided world, “an essential tool for cultural change.” While editing the volume, she learned that “the most biodiverse areas of world also are the most linguistically diverse . . . and those areas of the world are also the most threatened right now”—both the languages and the environment. Without local voices, the environmental movement is as weak as a monoculture of thousands of acres of corn. Human diversity and biodiversity go hand in hand.

Tuckey hopes that the publication of Ghost Fishing is just the beginning. “I hope that it sparks more conversation, more poems, and that it shifts how we think about who is an environmental poet and what is environmental poetry,” she said. In a poem from the volume, amidst our angry politics and the crumbling of the natural world, she makes a larger plea:

Teach me how to build an ark big enough

for everyone who needs rescue.

If Ghost Fishing at times takes on a tone of biblical apocalypse, it also uses religion to illuminate nature’s awesome power. Joy Harjo writes an ode to eagles who

swept our hearts clean

With sacred wings.

We see you, see ourselves and know

That we must take the utmost care

And kindness in all things

This is a vision of human stewardship—in this case from a Native American perspective—that is so lacking in today’s world. The Judeo-Christian tradition, too, can inspire a vision of a world torn between hope and destruction. So writes Everett Hoagland:

As our planet goes, so go we. Great Poet,

who inspired In the Beginning was The Word . . . .

Yet no poetic lyrics, however great, will restore the world we have placed in such dire threat. It will take a coalition, many peoples fighting hard and long. And poetry can be one means of inspiration.