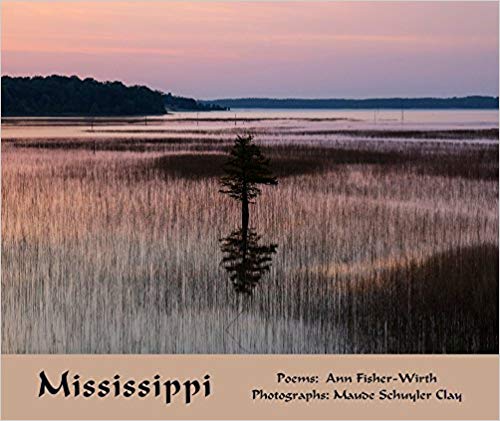

Anne M Carson recently wrote a review of Mississippi, poetry by Ann Fisher-Worth (BEI Emeritus Fellow) and photographs by Maude Schuyler Clay. Below is the review, for a link to the original post.

Forty-seven paired poems and photographs make up this beautifully realised work. Photographer Maude Schuyler Clay and Poet Ann Fisher-Wirth have collaborated to produce a book of Ecophotography and Ecopoetry – careful and moving testimony to the eponymous river, the landscape and its people who do inhabit and have inhabited it. The subjects of the poems are fictional, as the author’s notes explain. However many of them are based on history, or are inspired by people of importance to the authors.

The poems are set in the Mississippi Delta and its environs. Over many decades, the river has suffered considerable degradation and this is known first-hand by these artists, who live in the area. This degradation cannot, Fisher-Wirth tells us, ‘be separated from [the area’s] history of poverty and racial oppression’ (ix). The resulting ugliness and suffering are given place in the work, and are the depth against which the beauty in people and environment, can be plumbed.

Although each poem relates predominantly to the photograph on the facing page, and is complete in itself, it is not given a title. This means that the text is set free to flow in a single long thread from one page to the next – the voices drift into each other, like the river, like the generations.

The photographs combine both open land and riverscapes – often with empty buildings – and interiors. Many of the images are of commonplaces – petals dropped by a tree on a path, the curved shadow of window lace-work on a faded runner rug, the contours of everyday fruit in an ordinary bowl on a deal table. Sometimes they are of kitsch kewpie dolls or plaster and tinsel figurines. All the photos are rendered beautifully, regardless of subject matter. This is so even when the image shows what has contributed to the area’s degradation – cotton crops (with their association to slavery and implied fertiliser use), leading to algal blooms on waterways.

The quality of the images is not achieved by a photoshopped aesthetic, dressed up for the readers’ easy consumption. Rather we are invited to enter this complex world of beauty and ugliness, pleasure and suffering, and take in what we see. We are shown people’s stories in word and image, through the lens of understanding and compassion, so that we might deepen our empathy and understand the complexity.

Clay’s use of light has a haunting, muted quality, gained, as she says in an artist’s statement, by her preference to take photos in ‘the natural low light of early morning or late afternoon, “in the gloaming” as the Scots called it – the last rays of eery, orange light that blanket the evening before the sun disappears for the night’ (100). This gentles the lines and invokes a comparable approach from the viewer, making the photos memorable.

Her framing also invites the reader to engage beyond a first glance, to partake of the stillness of river shots. Or in others, to pose questions. She manages to allow the mystery of life to hover in the photos – not everything is disclosed and this intrigue deepens the reader’s engagement. The dog for instance is alert, solitary, in a riparian setting. What accounts for its downcast expression? The accompanying poem, poignantly reads:

… I don’t need to be feeding

no dog that won’t hunt …

… leave em behind

you know what I mean?

(10)

Although much domestic and other human detail is represented in the imagery, there is only one actual portrait. A young woman lies on a rug on the grass, having fallen (the poem tells us) for the German Artist who came to her school and gave her a freedom-vision. The poem captures her voice and its scorn for all that her parents and the school represents, through her disdain for cotillion square dancing. What a world of teenage pain is captured economically in its invocation!

People are not represented visually in the photos but the work is a community of monologues, bringing life to voice and in so doing honouring the Mississippi inhabitants – White, Native American and African American people alike. The representative voices endow the text with aural richness as the cadences flow and stutter onto the page and into the ear. A self-confessed sinner tells us poetically that, ‘Devil he put the stars out / take away the moon’ (58). The (also self-confessed) dumbass describes being so pissed when his ‘skanky ho’ leaves him that he inadvertently shoots his own window out. The collection reminds me of Rilke’s work ‘The Voices’, a series of poems in the voice of people who don’t usually get to express a voice, characters excluded from mainstream narratives. Fisher-Wirth’s poems aren’t afraid to use the real language of these people, which hasn’t been dressed up to suit a more mainstream readership. The complexity of economic and environmental pressures are woven into the narratives, helping to contextualise some of the meanness – this is an honouring too.

But there is eros and gentleness also. Sometimes stress is met with a kind and loving gesture instead of a violent one, and nature is seen as solace. One partner, ‘that sweet man’ rescues a woman from a domestic meltdown (86). He,

puts us in the truck and drives us to the lake

Breathe he tells me

baby breathe

and look at it just look at it

(86)

Voices, and other soundscapes are strong in the poems. In one poem, for instance, a woman whipping up egg whites is used as a simile for the vociferous insects. These sounds drench the poem in aural plenitude.

the cicadas in the privet and pecan trees

whupping up their little motors …

like beating the eggs for angel cake…

(82)

One of the most moving poems in the collection gives voice to a woman who fears dementia will disinhibit her. She’s scared she’ll start thinking like her mama did and that these words will flow uninvited from her mouth:

words I grew up with

along with croquet in the summer,

crystal swans and silver salvers—

(68)

Her evocation of her mother brings those violent, racist times into the book, preventing them from being forgotten and reminding us that today’s racism has long roots.

The last poem in the book is particularly evocative, as is the photo with which it rubs shoulders. An old house sits on a field, its furrows filled with liquid light. ‘[N]ow as the seasons pass’, Fisher-Wirth says, ‘the husk remains’ – a comment both on time and its depredations in all things and the house itself. It is now just a shell open to the elements, where once it was a home – ‘she laid plates on the table’, and ‘he scraped rancid mud from his shoes’ (94). The quotidian becomes elegiac, a note frequently sounded in both poems and images here. The poem goes on to say:

Light shines through walls

from which boards are missing

(94)

This couplet beautifully sums up what I have most enjoyed in this work – the permeability which is at its heart – images, people, things. Permeability also reflected in the aesthetic of the poems themselves – sparsely punctuated, relying on white space to do the work of timing and dramatic unfolding. The poems are spacious and tend to the contemplative, fitting counterpoints, and sharing a similar energy, to the photographs.

The final pairing is inspired. Fisher-Wirth’s poem is reminiscent of the poignant tanka by Izumi Shikibu, ‘Although the wind …’, which also uses the image of a ruined house and what its permeability opens us to. Jane Hirshfield observes of this poem that it ‘exchange[s] certainty for praise of mystery and doubt’, stepping ‘back from hubris and stand[ing] in the receptive, both vulnerable and exposed’.[i] Fisher-Wirth’s poem and Clay’s image describe a house in decrepitude, but though in decline, the poem does not leave us with grief. Rather, it achieves a remarkable transformation, which is one of poetry’s main wonders. What we are left with is uplifting – literally – to a sky, ‘drenched and pulsing’. And ‘Light, snak[ing] away from the house / in watery furrows‘ (94). The poem’s final exhortation is to the light as a possible life-guide. If you followed it, it asks, ‘what would you find there’ (94). It leaves the question hanging, without even a punctuation mark to close it off. It is a superb and open place to end.